1. Maurer M, Magerl M, Betschel S, Aberer W, Ansotegui IJ, Aygören-Pürsün E, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema-The 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77(7):1961–90.

2. Bork K, Anderson JT, Caballero T, Craig T, Johnston DT, Li HH, et al. Assessment and management of disease burden and quality of life in patients with hereditary angioedema: a consensus report. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):40.

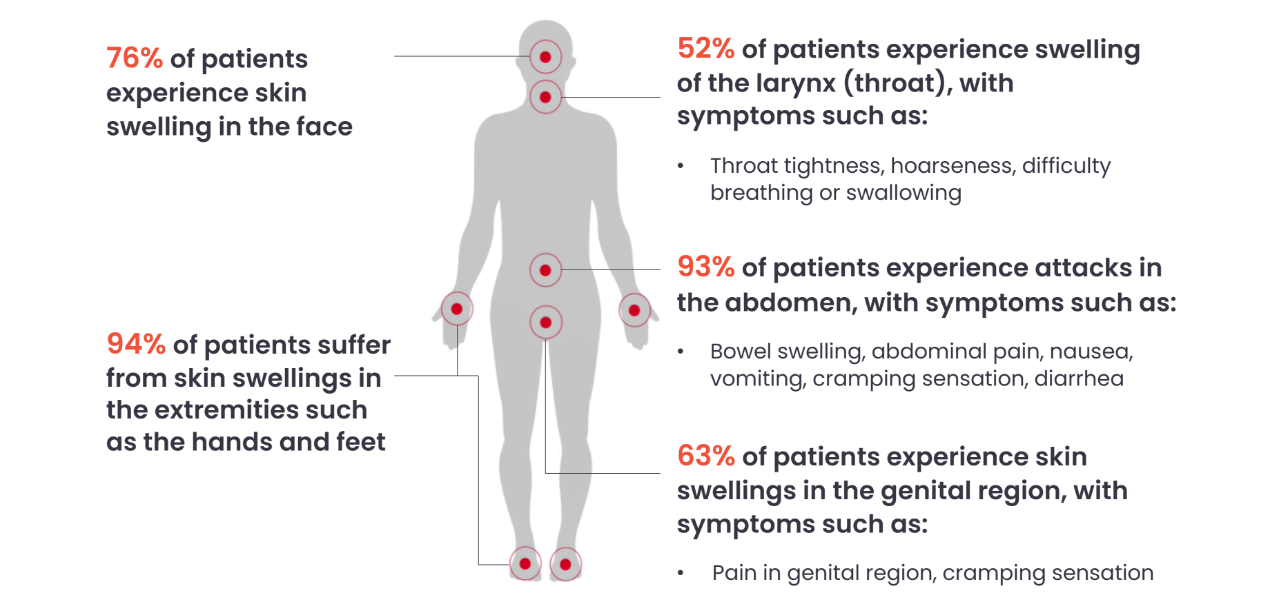

3. Azmy V, Brooks JP, Hsu FI. Clinical presentation of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020;41(Suppl 1):S18-s21.

4. Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary Angioedema: New Findings Concerning Symptoms, Affected Organs, and Course. Am J Med. 2006;119(3):267-74.

5. Bernstein JA. Severity of hereditary angioedema, prevalence, and diagnostic considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(14 Suppl):S292-s8.

6. Mendivil J, Murphy R, de la Cruz M, Janssen E, Boysen HB, Jain G, et al. Clinical characteristics and burden of illness in patients with hereditary angioedema: findings from a multinational patient survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16(1):94.

7. Zanichelli A, Longhurst HJ, Maurer M, Bouillet L, Aberer W, Fabien V, et al. Misdiagnosis trends in patients with hereditary angioedema from the real-world clinical setting. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(4):394-8.

8. Bork K, Hardt J, Witzke G. Fatal laryngeal attacks and mortality in hereditary angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):692-7.

9. Farkas H. Management of upper airway edema caused by hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):19.

10. Magerl M, Doumoulakis G, Kalkounou I, Weller K, Church MK, Kreuz W, Maurer M. Characterization of prodromal symptoms in a large population of patients with hereditary angio-oedema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39(3):298-303.

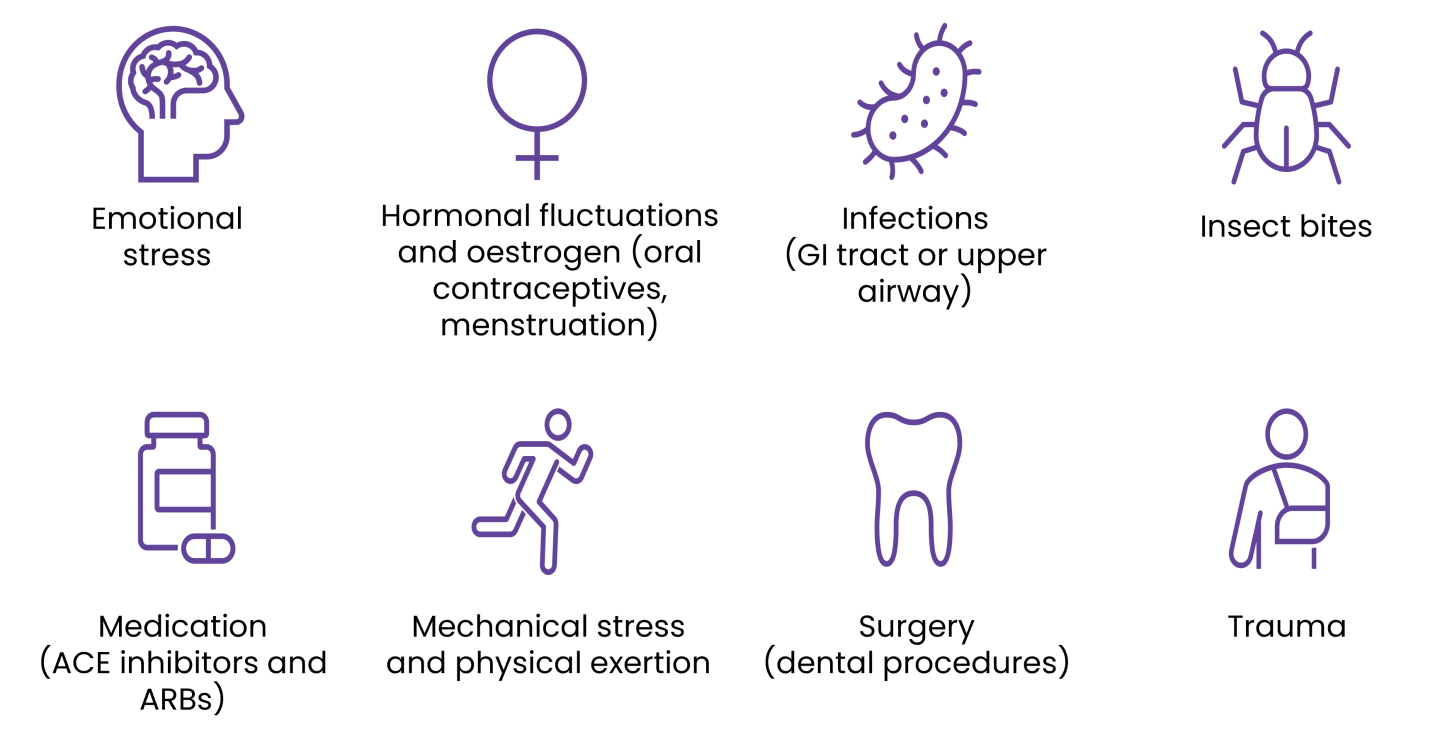

11. Zotter Z, Csuka D, Szabó E, Czaller I, Nébenführer Z, Temesszentandrási G, et al. The influence of trigger factors on hereditary angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:44.

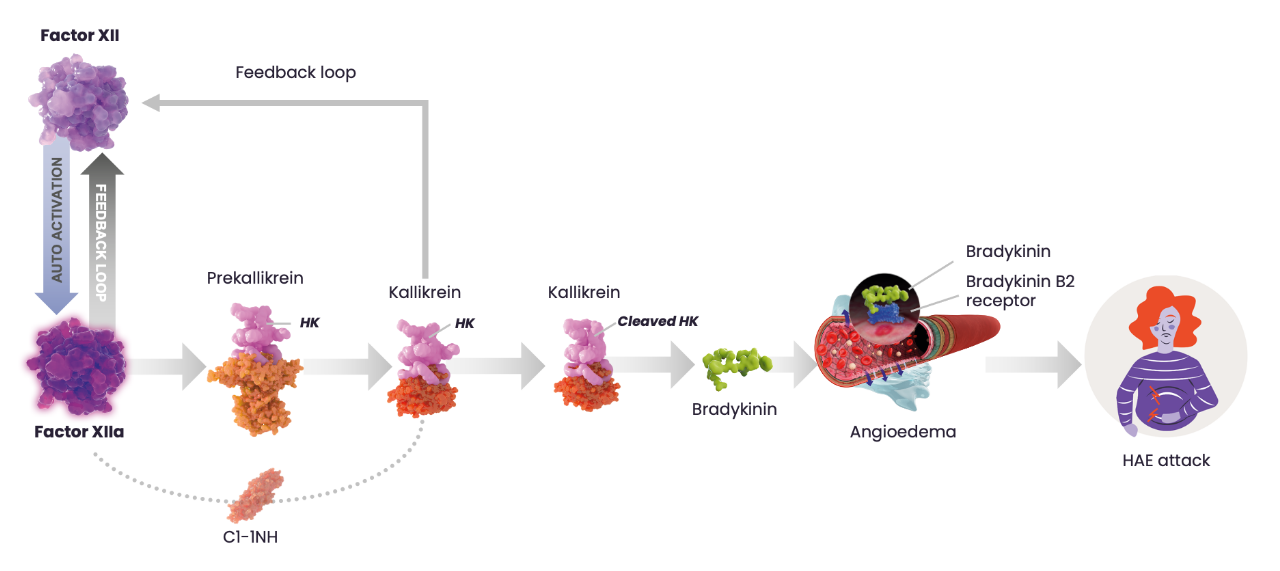

12. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary Angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1136-48.

13. Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1027-36.